6 April – 25 May 2024

6 April – 25 May 2024

Rämistrasse 5

8001 Zurich · Switzerland

6 April – 25 May 2024

Artist Talk: 2 May, 6.30 pm

Closed on 1 May + 9 May

–

Tue-Fri: 11 am–6 pm

Sat: 11 am–5 pm

The exhibition comprises around ten mostly recent artworks, some of which belong to particular series and have an obvious similarity, while others appear so dissimilar that prior knowledge is required in order to link the presentation to a single artist. There is a very specific reason for this diversity: for many years, the art of Marcel Duchamp – which is nothing other than the manifestation of his thinking – has been not only one of the main subjects of Bethan Huws’ work, but also its model. Duchamp said that the choice of a ready-made – which in his (and Huws’) opinion was probably his most important contribution to twentieth-century art – was made according to the criterion of aesthetic indifference. An artistic style (such as Impressionism or Cubism) was thus replaced by a way of thinking that has an unmediated, individual relationship to things and is shaped by them. The primacy of thinking is what underlies the aesthetic nonuniformity of the works in Bethan Huws’ exhibition.

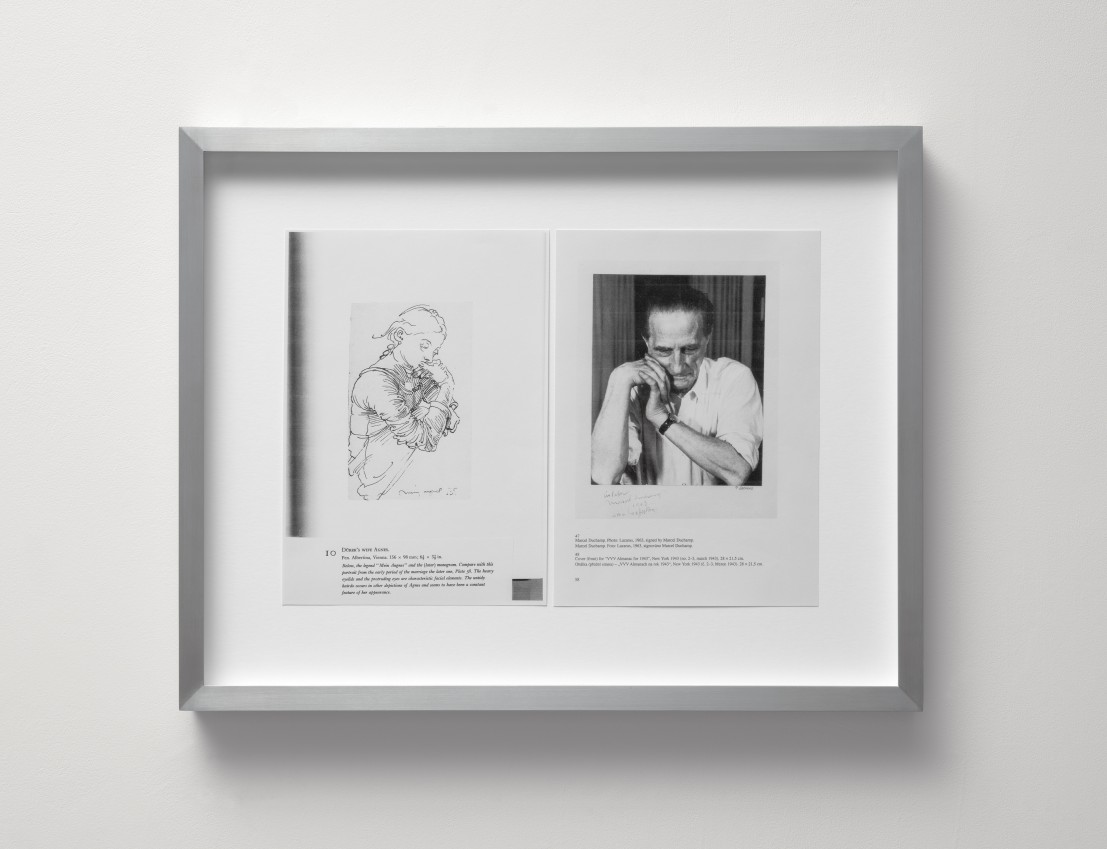

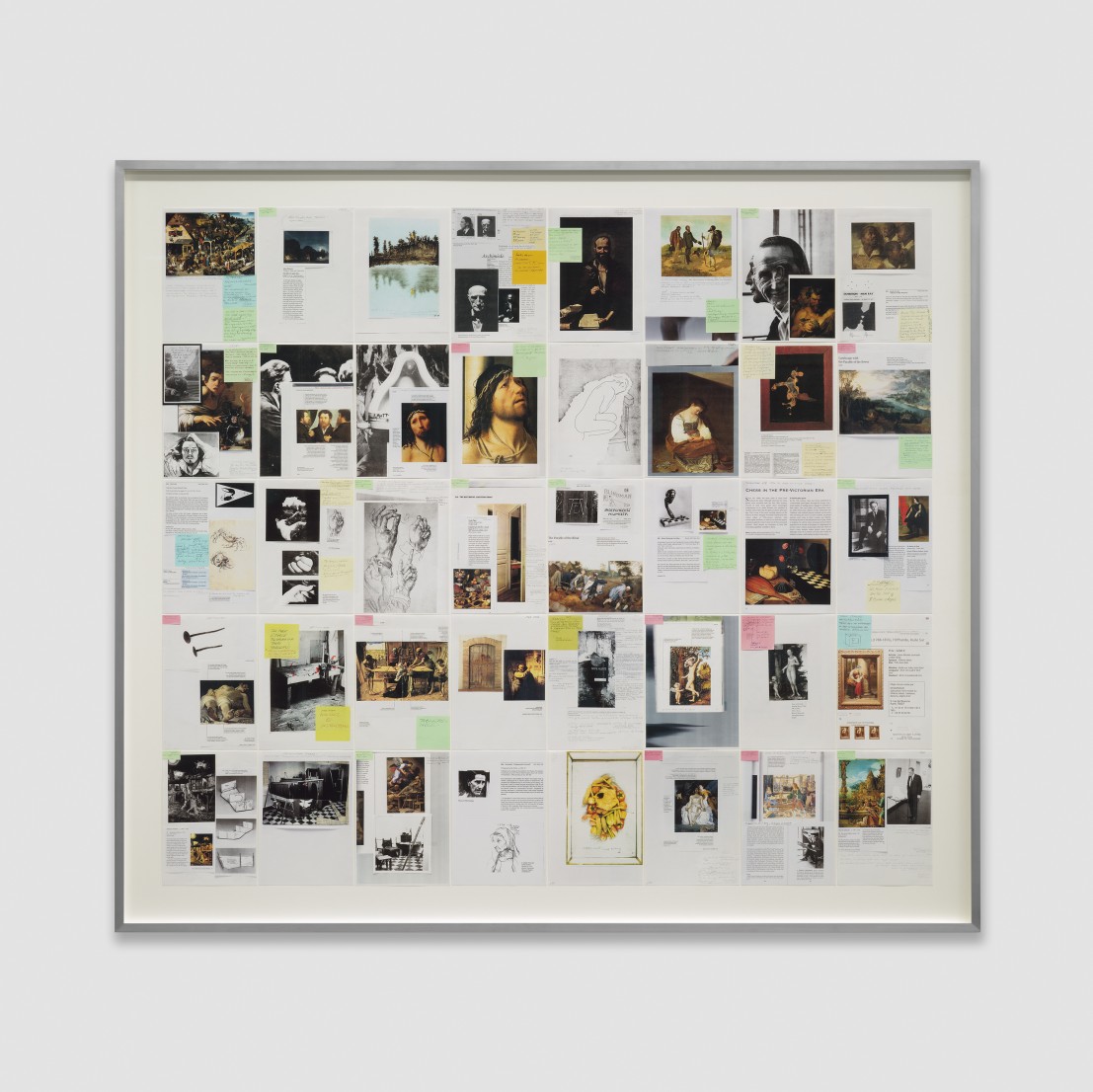

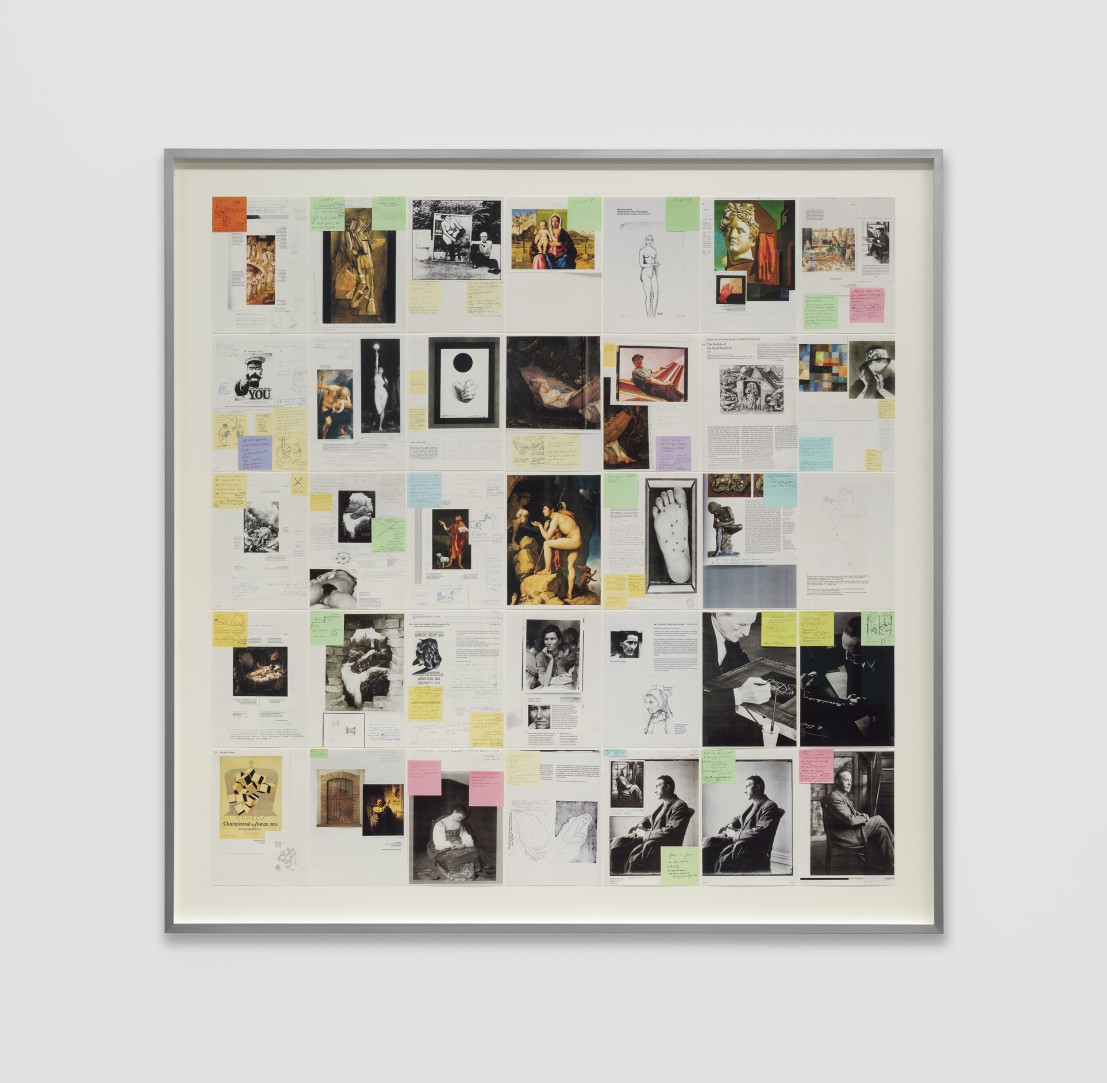

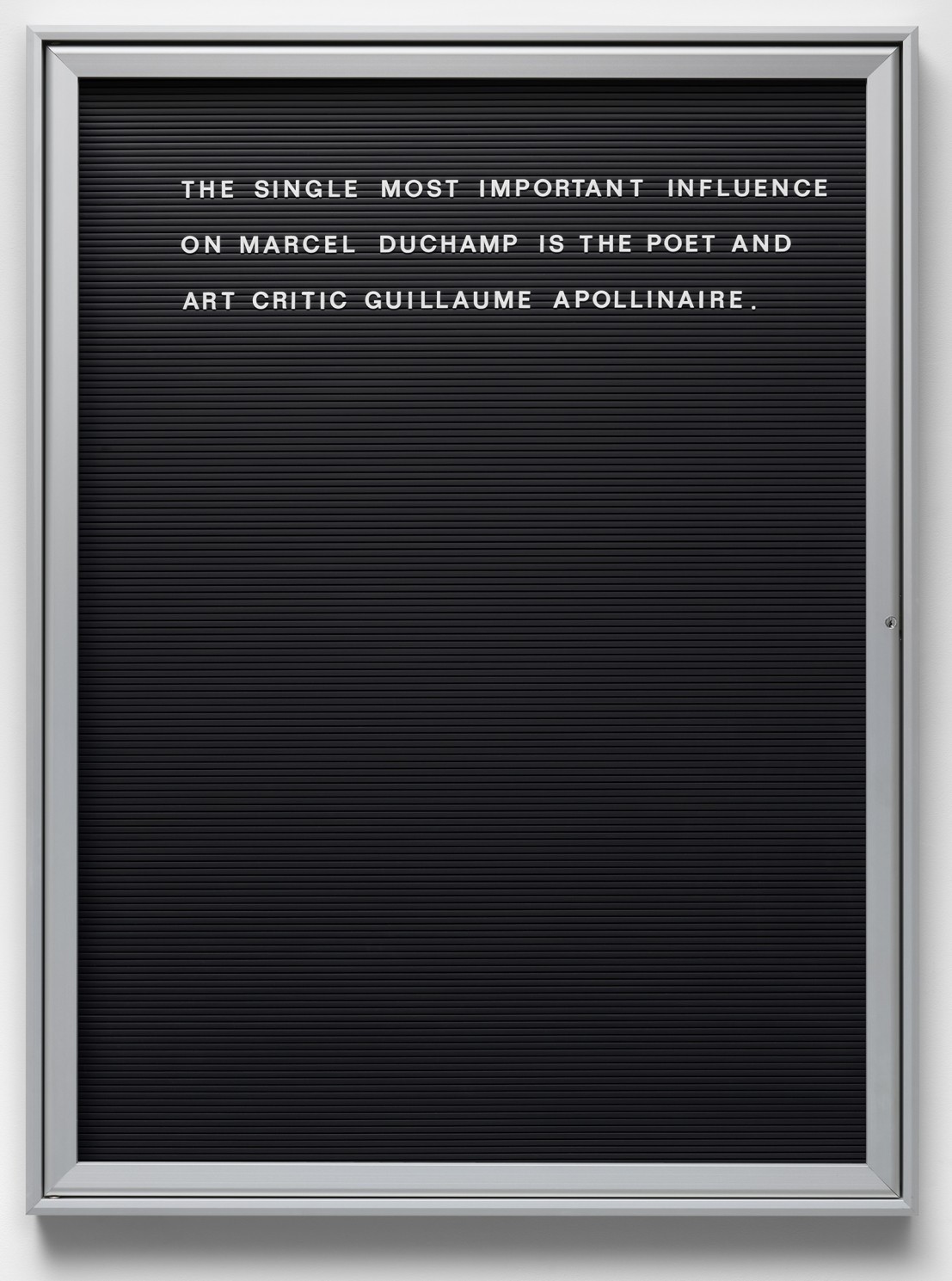

The selection of works on display is such that despite (or precisely because of) their diversity, they give a valid, albeit incomplete, picture of Huws’ artistic practice. In her Panel works, she presents collections of notes that attest to the exceptional, groundbreaking and exemplary qualities of Duchamp’s thinking. These pieces take up Duchamp’s notion of the ready-made, in that the exhibited A4 sheets are not originals, but rather printed copies of Huws’ notes, including a number of coloured Post-its. In her Research Notes, Huws untangles the web of relationships in which, she believes, not only Duchamp’s artworks are embedded, but also the things he said in conversations and texts, and even his photographic (self-)stagings, as mundane and unintentional as these may initially appear. The image Huws creates of Duchamp’s output is characterised by a complete absence of coincidence and arbitrariness: everything that emanates from Duchamp is, she maintains, intentional, as if it were subject to an inescapable compulsion. Huws says: “It’s there for a reason and it’s for us to find the reason.”

Reflection Panel presents numerous examples that are intended to show how Duchamp responds to a given orientation towards the left by producing an orientation towards the right, and vice versa. As the hand of John the Baptist (the Precursor of Christ) in Matthias Grünewald’s painting is pointing left, the hand in Duchamp’s final painting, Tu m’, points to the right, and because the body in Courbet’s L’Origine du monde (The Origin of the World) is placed diagonally to the right, the body in Duchamp’s Étant donnés (Given) is oriented towards the left. Huws regards this right/left correlation as a relationship of reflection – in the sense of mirroring, but also in the sense of consideration or contemplation. By establishing mirror relationships in many situations that are otherwise completely unconnected, Duchamp reflects how he thinks: like a mirror, he creates a correspondence with the chosen objects, but does not intervene (as an artistic style does) with some kind of judgement, interpretation or standpoint. The perfect form of reflection is achieved, however, when the object stands for itself – as realised by Duchamp in the ready-made.

In Painting Panel, Huws explores how and to what extent Duchamp establishes relationships with paintings that are important to him, even when this involves what seem to be completely involuntary gestures. One example is the stain of his own ejaculate that constitutes Paysage fautif (Faulty Landscape) – a work he produced for the deluxe edition of the Boîte-en-valise (Box in a Valise). Huws suggests that the stain in Paysage fautif has been assimilated to the shape of the body of water in the landscape painting Parable of the Sower by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. This deliberate coincidence invites us to consider Duchamp’s masturbatory parable of art or thinking in relation to the creative act in imitation of Christ.

Reflection Panel establishes Duchamp’s thinking as a mode of reflection that maintains the undistorted integrity of things. Painting Panel, on the other hand, points to the multiple instances that determine Duchamp’s choices (choices concerning his work and, more broadly, the orchestration of his life). Tracing the reasons for his choices can be understood as Huws’ way of supporting the opposition to interpretation.

Lying on the floor of the exhibition space near Painting Panel is Bic Blue, the blue-coloured urinal Huws has created by fusing different variants of Duchamp’s ready-made Fountain. As early as 1917, Fountain was described as a “veiled Virgin”. This leads Huws to the blue of the Virgin’s robe, but also to the colour of the Bic pen – a well-known French invention – and hence to her own writing and thinking, and finally to the colour that is associated with mourning and melancholy. For Huws, the notion of ‘immaculate conception’ belongs in this context. The word ‘conception’ is of course also related to thinking, and Duchamp’s thinking is immaculate in that it incorporates things without any distortion: the choice of a ready-made is such an instance of immaculate conception. If Duchamp’s way of thinking is one that excludes all arbitrariness and vagueness, then Huws continues this mode of thinking in her own practice with the work Bic Blue. Like a dream image, Bic Blue condenses references that acknowledge the exemplary character of Duchamp’s work and simultaneously express the sadness that his acceptance of the factual – how things are – finds no echo in the real world.

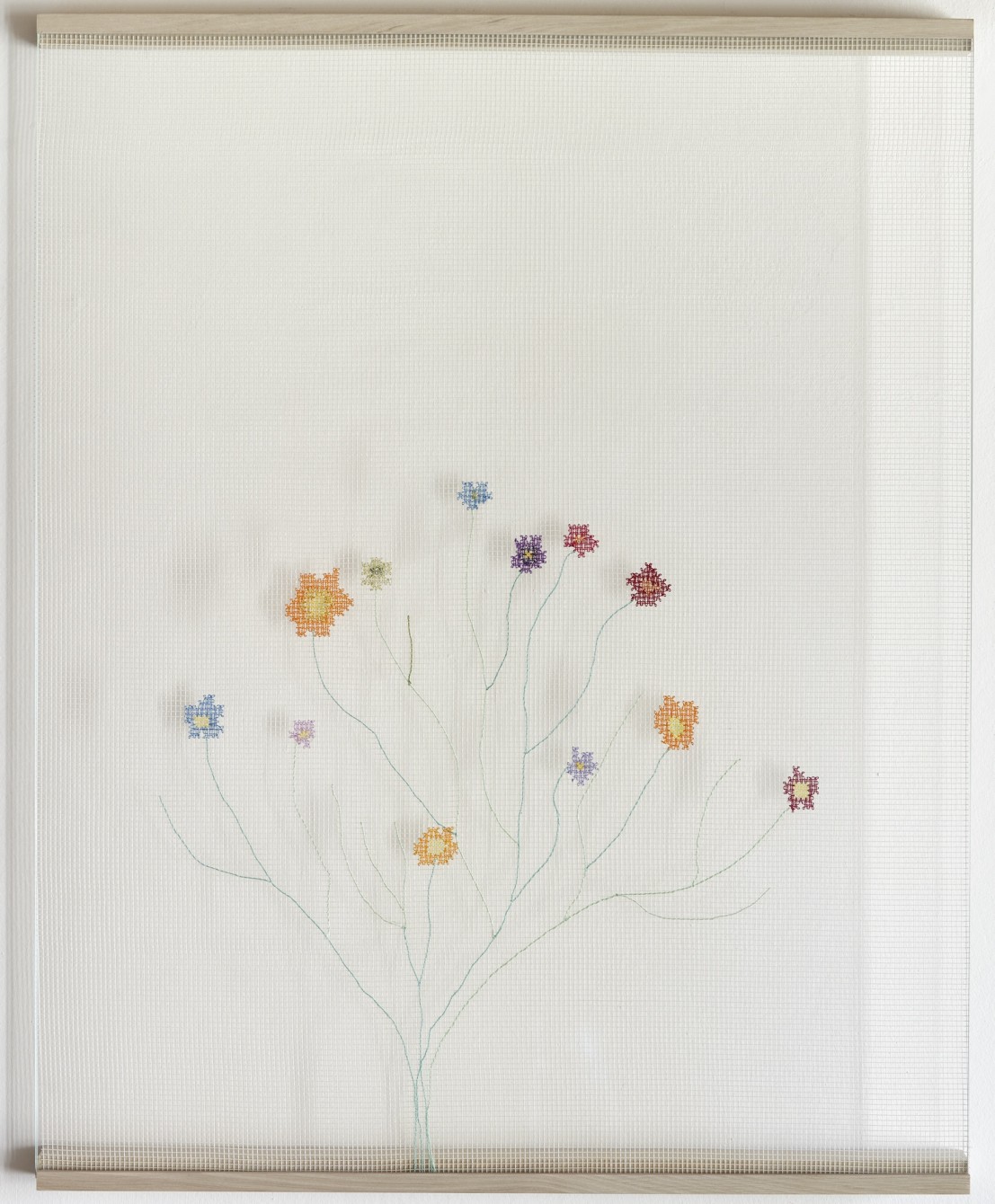

Duchamp’s originality consists in countering established forms of original creation with reflection (contemplation and mirroring). Undistorted rendering is, however, something entirely different from imitation. To give visual form to this unthinking dependency, Huws uses a medieval depiction of monkeys she saw in the Grossmünster in Zurich. Translated into neon tubing, the relief work from the church is to be read as an allegory of aping. Huws finds similarly direct significance in images drawn by a homeless man and a little girl, which she has had made into works of embroidery. The simple, indisputable statements in Huws’ Word Vitrines, meanwhile, present a linguistic equivalent to the aesthetic indifference of the ready-made.

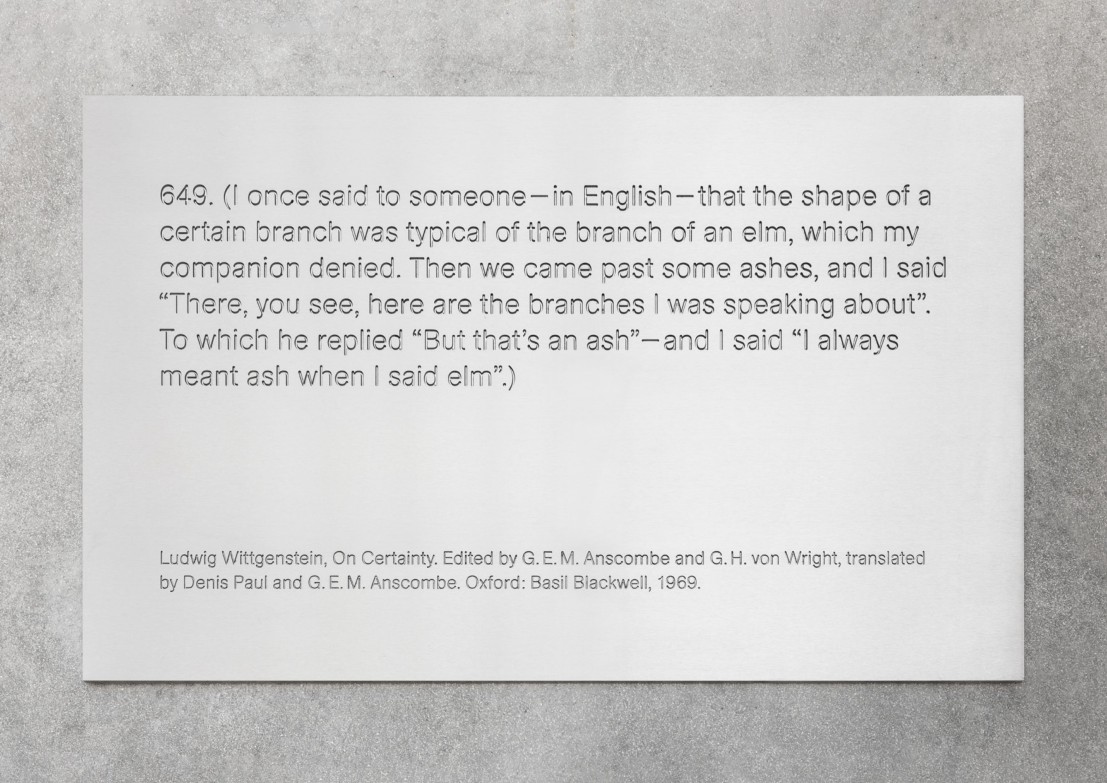

In Huws’ work The Ash and the Elm, the difficulty of obtaining certainty about an utterance leads her to a quote by Ludwig Wittgenstein. It comes from a section of his writings Über Gewissheit (On Certainty) that deals with the subject of errors. A speaker who has chosen the wrong name for a tree, yet means the right one, rectifies his error by switching from linguistic designation to demonstrative indication: “There, you see, here are the branches I was speaking about.” In our mind’s eye, we can see him making the very same gesture that Duchamp included in his painting Tu m’ – an extended index finger – and it would come as no surprise if a visitor to the current exhibition were to point at the trees placed next to the text panel and ask: “So, which one is the ash?” The gesture used to point at something in order to obtain certainty about it is the same one Duchamp used when choosing a ready-made.

The defining characteristic of Huws’ presentation of aesthetically diverse works is reflection – or, more precisely, reflection upon reflection.

–

by Ulrich Loock, Translation by Jacqueline Todd

neon tube mounted on aluminium-plexiglass support, transformers

225 × 340 × 12 cm

1/2 (+1AP)

BH/P 164

two A4 notes, colour inkjet print on cotton paper Innova IFA24 210gms, mounted on museum cardboard, aluminium frame with museum glass

45.8 × 58.3 × 5 cm

1/3 (+1AP)

BH/F 22

1/3 (+1AP) sold

2/3 (+1AP) available

forty A4 notes, colour inkjet print on cotton paper Innova IFA24 210gms, mounted on museum cardboard, aluminium frame with museum glass

190 × 205 × 5 cm

1/2 (+1AP)

BH/F 20

thirty-five A4 notes, colour inkjet print on cotton paper Innova IFA24 210gms, mounted on museum cardboard, aluminium frame with museum glass

170 × 169 × 5 cm

1/2 (+1AP)

BH/F 21

collage (photocopied notes, Post-its, postcard…), mounted on museum cardboard, aluminium frame with museum glass

120 × 87 × 4 cm, each

BH/D 161

stainless steel plate with engraved text, trees, pots

plate 60 × 100 cm

dimensions variable

1/3 (+1AP)

BH/S 139

Aluminium, glass, rubber and plastic letters

100 × 75 × 4.5 cm

1/2 (+1AP)

BH/P 186

embroidery, glass, wood

62.5 × 51 × 3 cm

HC (Ed. of 2)

BH/S 125

embroidery, glass, wood,

57 × 69 × 3 cm

Unique (+1HC)

BH/S 123

We are very sorry.

Unfortunately, your browser is too old to display our website properly and to use it safely.

If you are using Internet Explorer, we recommend updating to its successor Edge or switching to Firefox, Chrome or Brave. If you surf with Safari, we recommend updating or even switching to one of the above browsers.

Galerie Tschudi

Contact Page×