To Every Earth its Blood

1 APRIL – 20 MAY 2023

Zürich

The work of Kemang Wa Lehulere (*1984) engages with the history of his home country, South Africa, in a space situated between tracing personal histories and historical events. The artist creates haunting visual narratives that he subjects to an ongoing process of revision and reconstruction.

Kemang Wa Lehulere has been been part of solo and group exhibitions and has been internationally aclamied and awarded. In 2017, he was Deutsche Bank’s ‘Artist of the Year’, recieved the fourth Malcolm McLaren Award and was a finalist in the Future Generation Art Prize in Kyiv, Ukraine. He is the winner of the 2015 Standard Bank South Africa, Young Artist Award and is one of two young artists awarded the 15th Baloise Art Prize at Art Basel in 2013. To date, he has had solo exhibitions at Göteborg Konsthall, Sweden, Tate Modern, UK, the Pasquart Art Centre, Switzerland, MAXXI, Italy, the Deutsche Bank KunstHalle, Germany and the Art Institute of Chicago, USA. Selected group exhibitions include Centre Pompidou, Paris, 58th Venice Biennale, A4 Arts Foundation, Cape Town, Performa 17, New York, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, among others.

1/35

bronze, brass

130 × 30 × 30 cm (each)

3/3

KW/S 33

2/35

Wood from salvaged school desks, 70 × 60 × 48 cm

KW/S 27

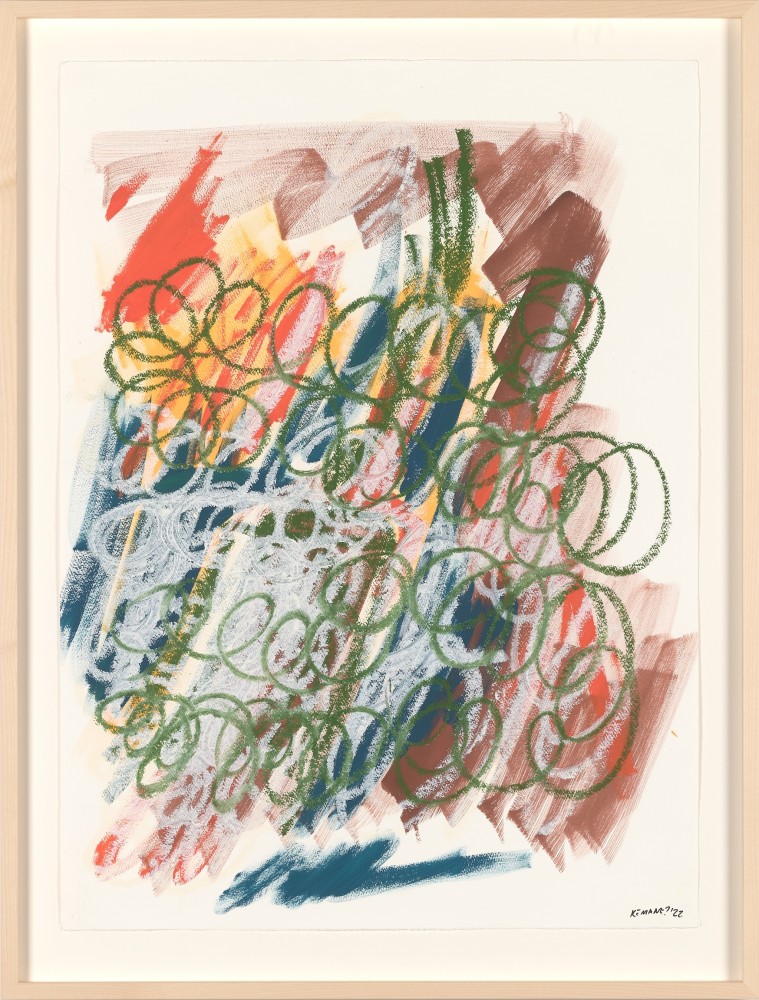

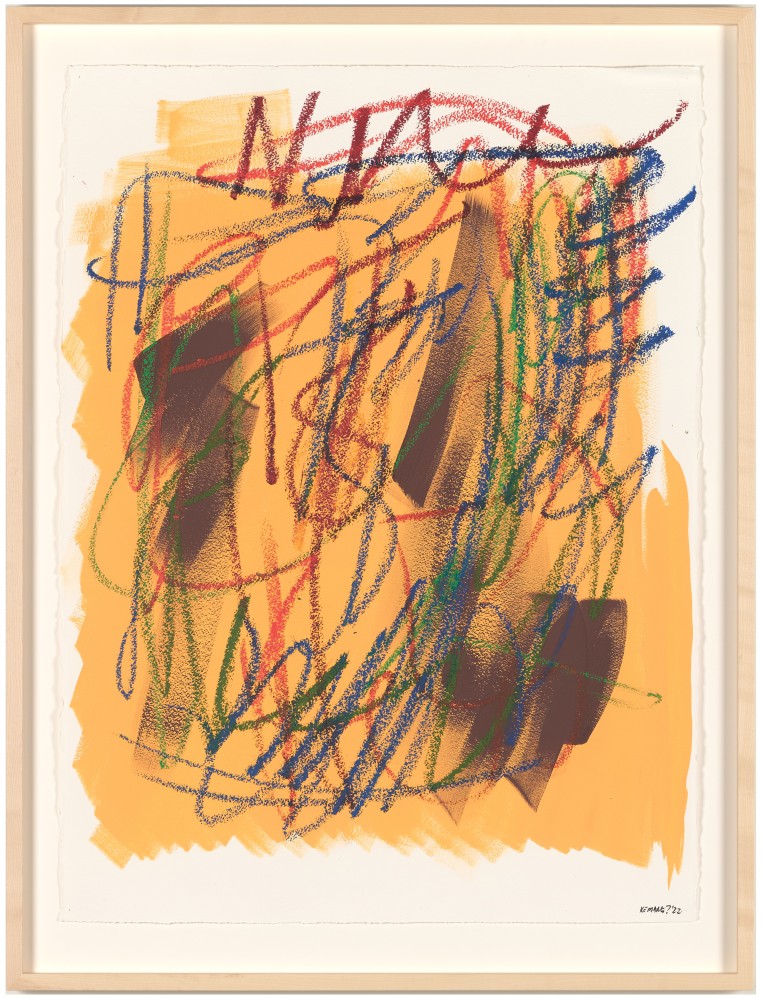

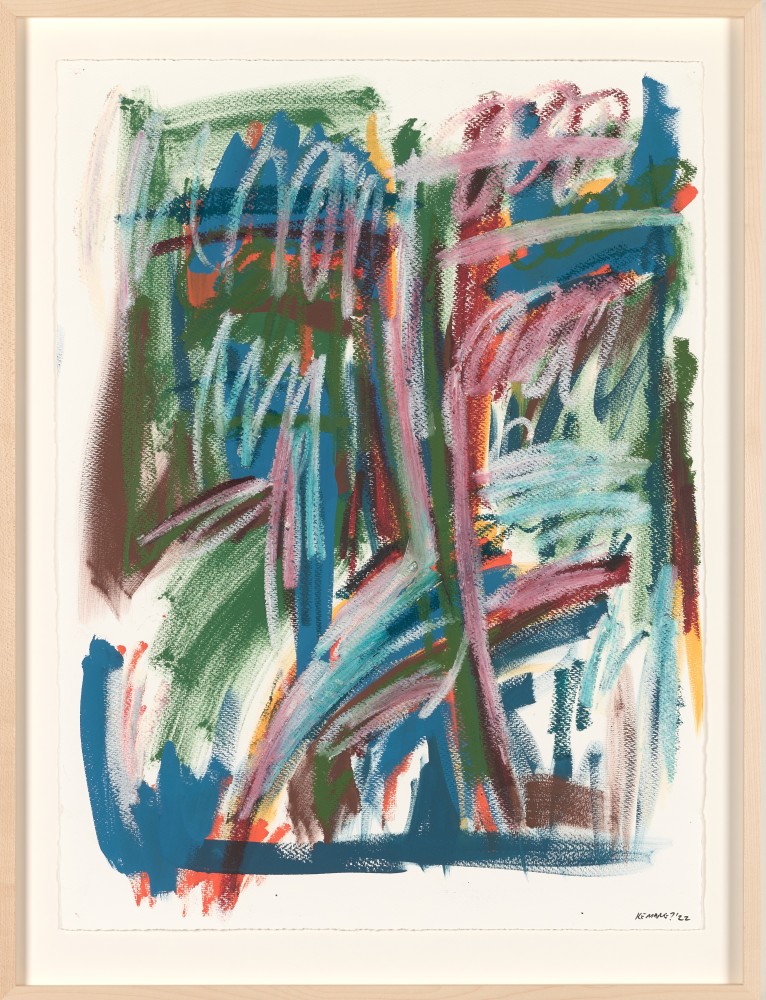

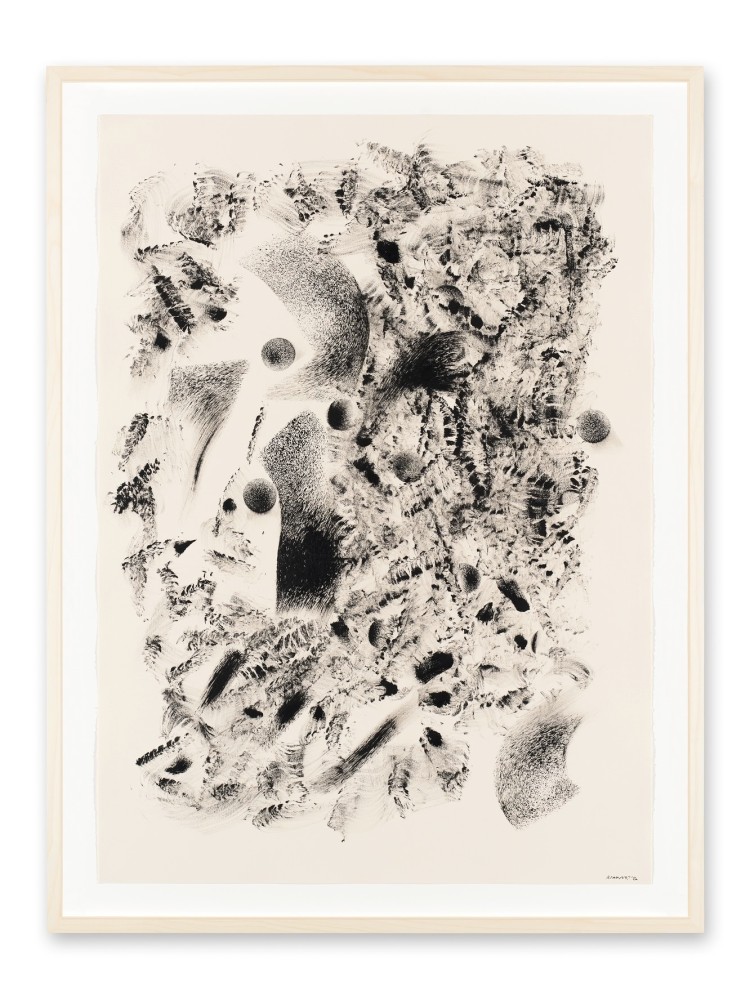

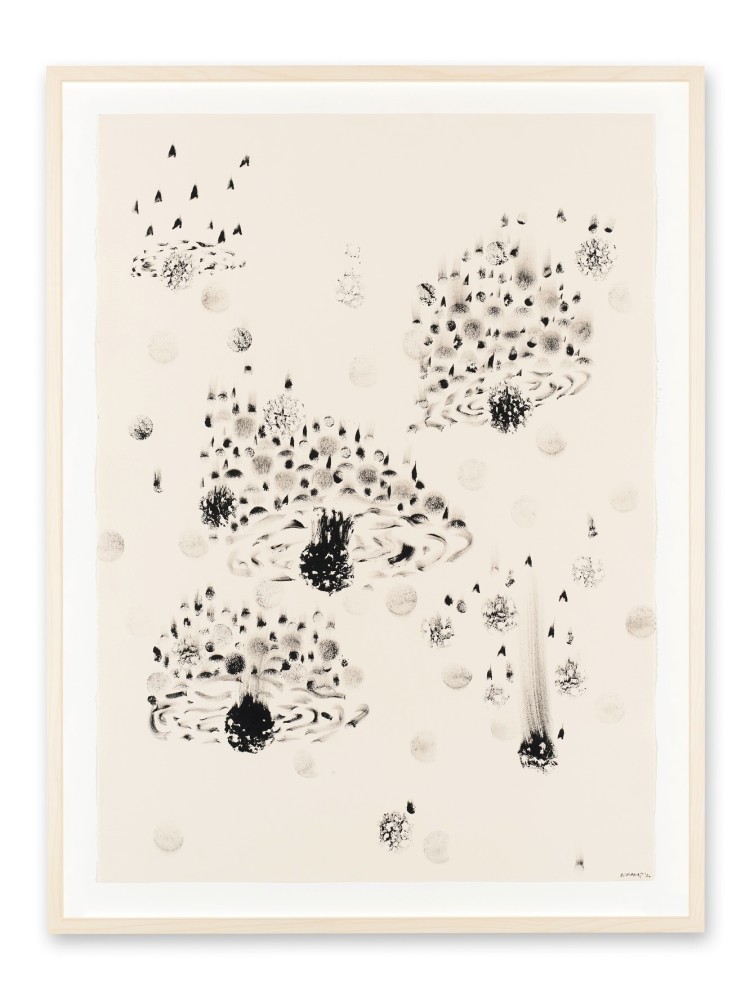

3/35

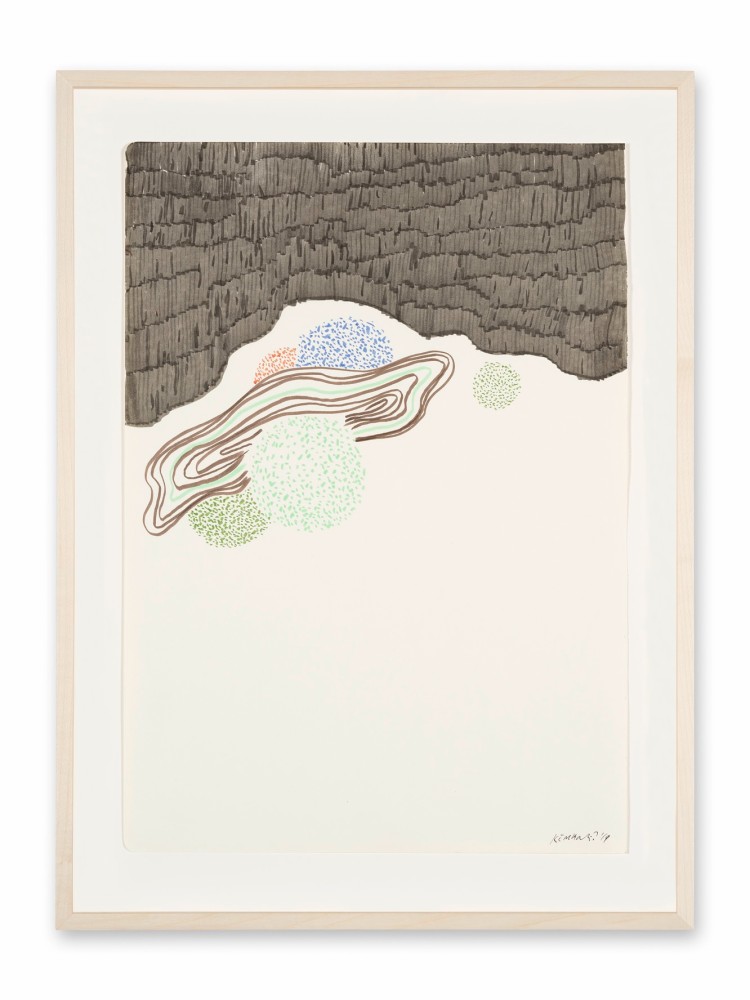

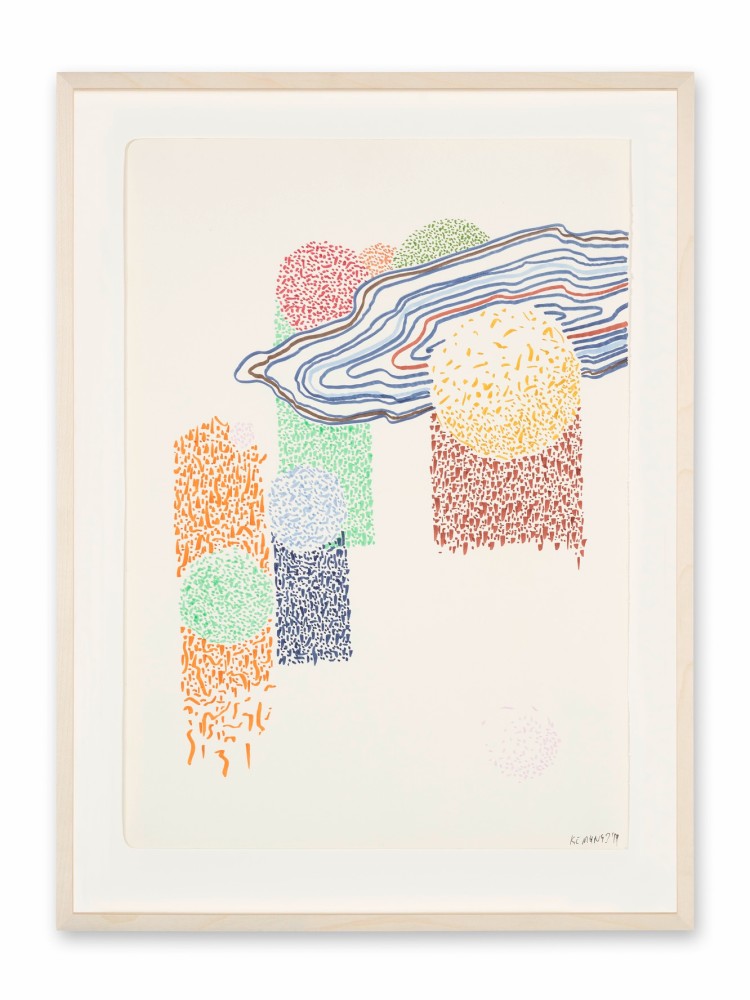

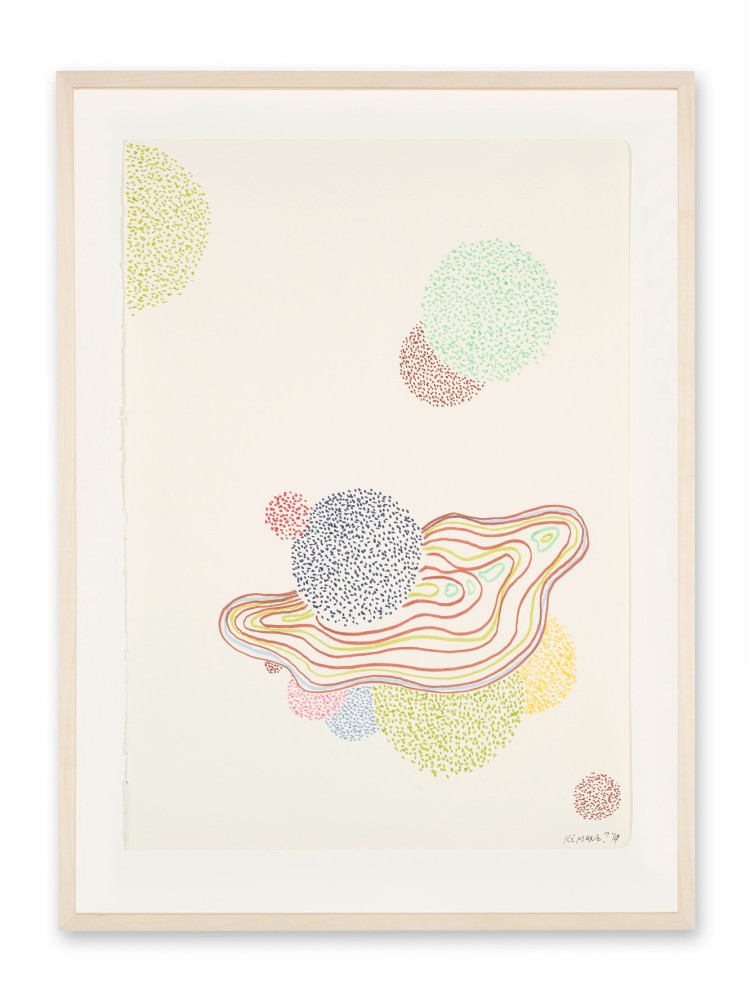

ink and oil on paper, 76,5 × 57 cm / 87,7 × 66,7 × 3,5 cm (framed)

KW/D 59

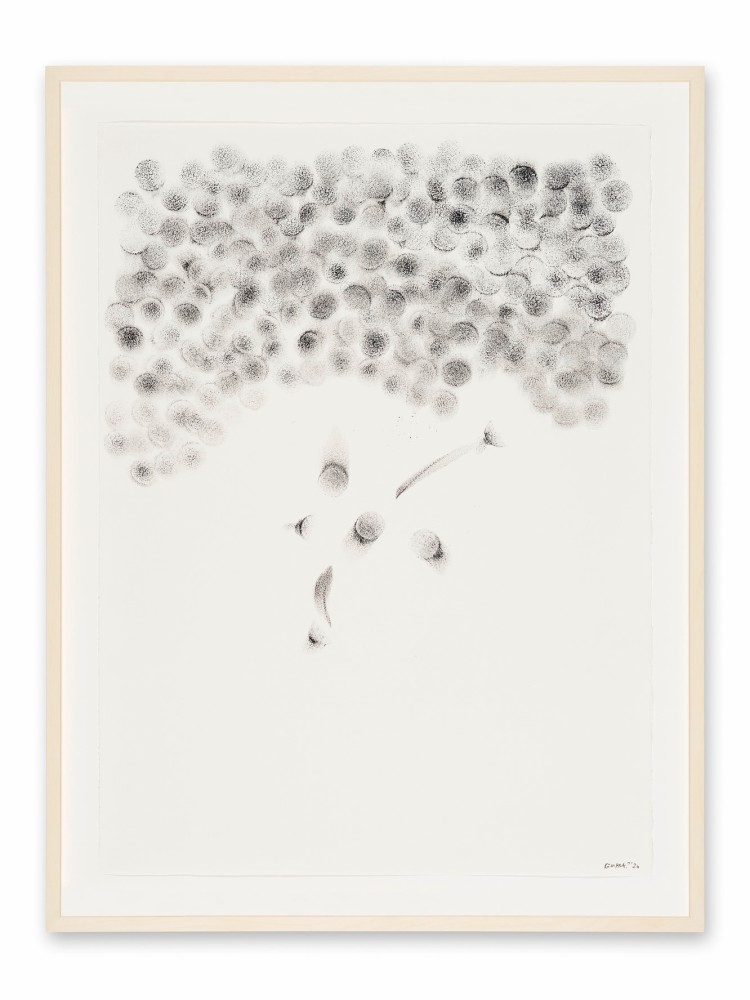

4/35

ink and oil on paper, 76,5 × 57 cm / 87,7 × 66,7 × 3,5 cm (framed)

KW/D 66

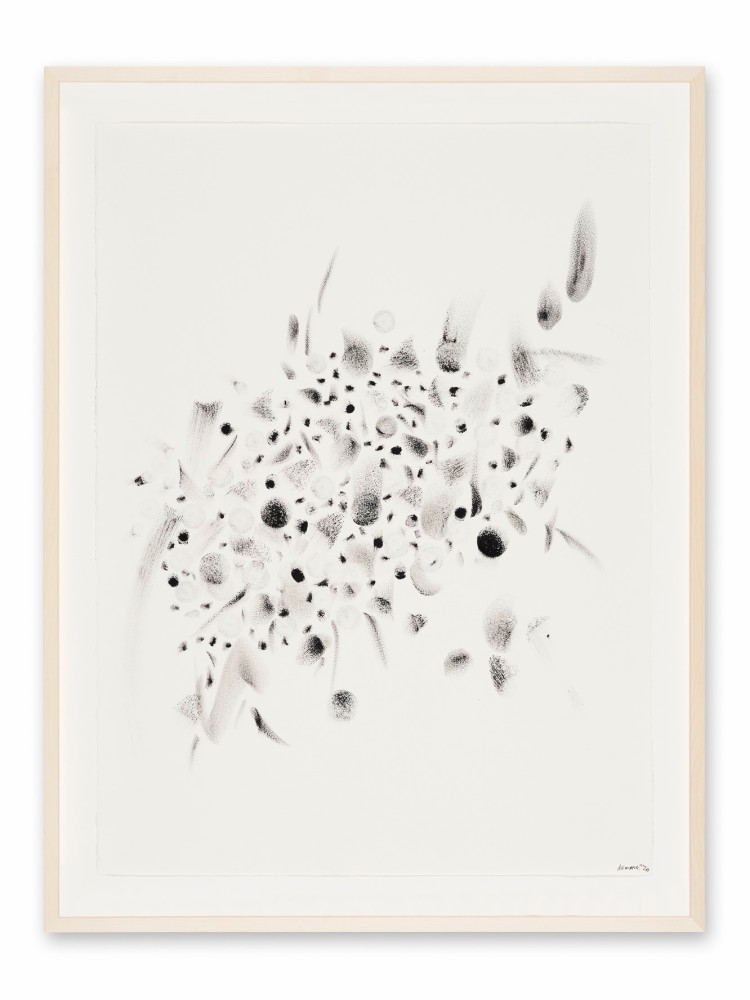

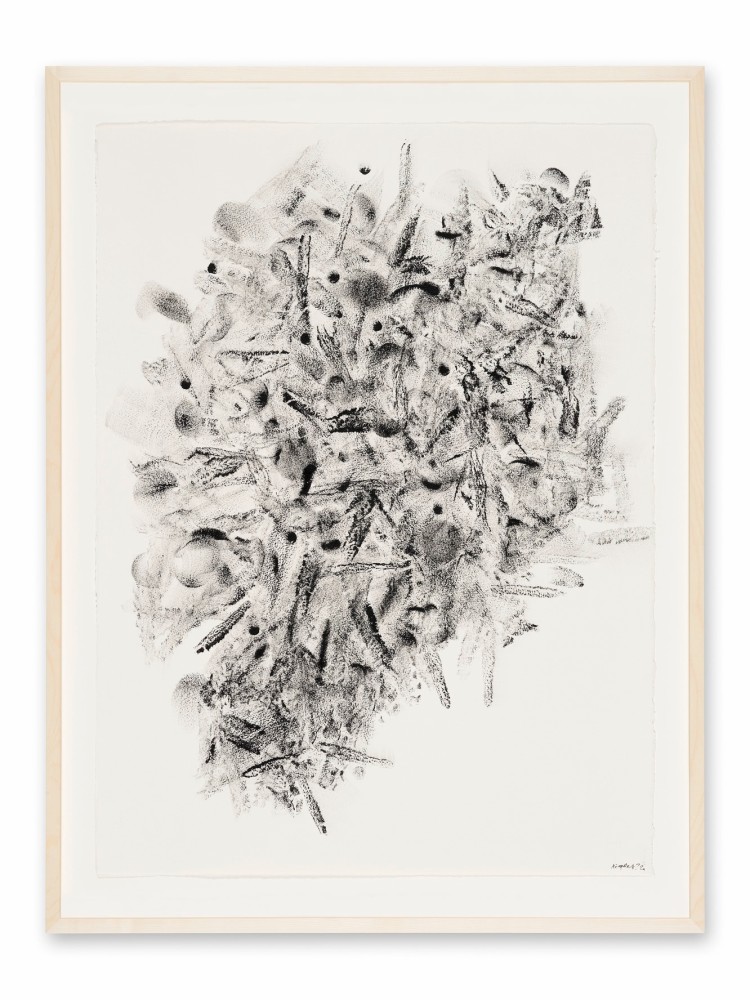

5/35

ink and oil on paper, 76,5 × 57 cm / 87,7 × 66,7 × 3,5 cm (framed)

KW/D 56

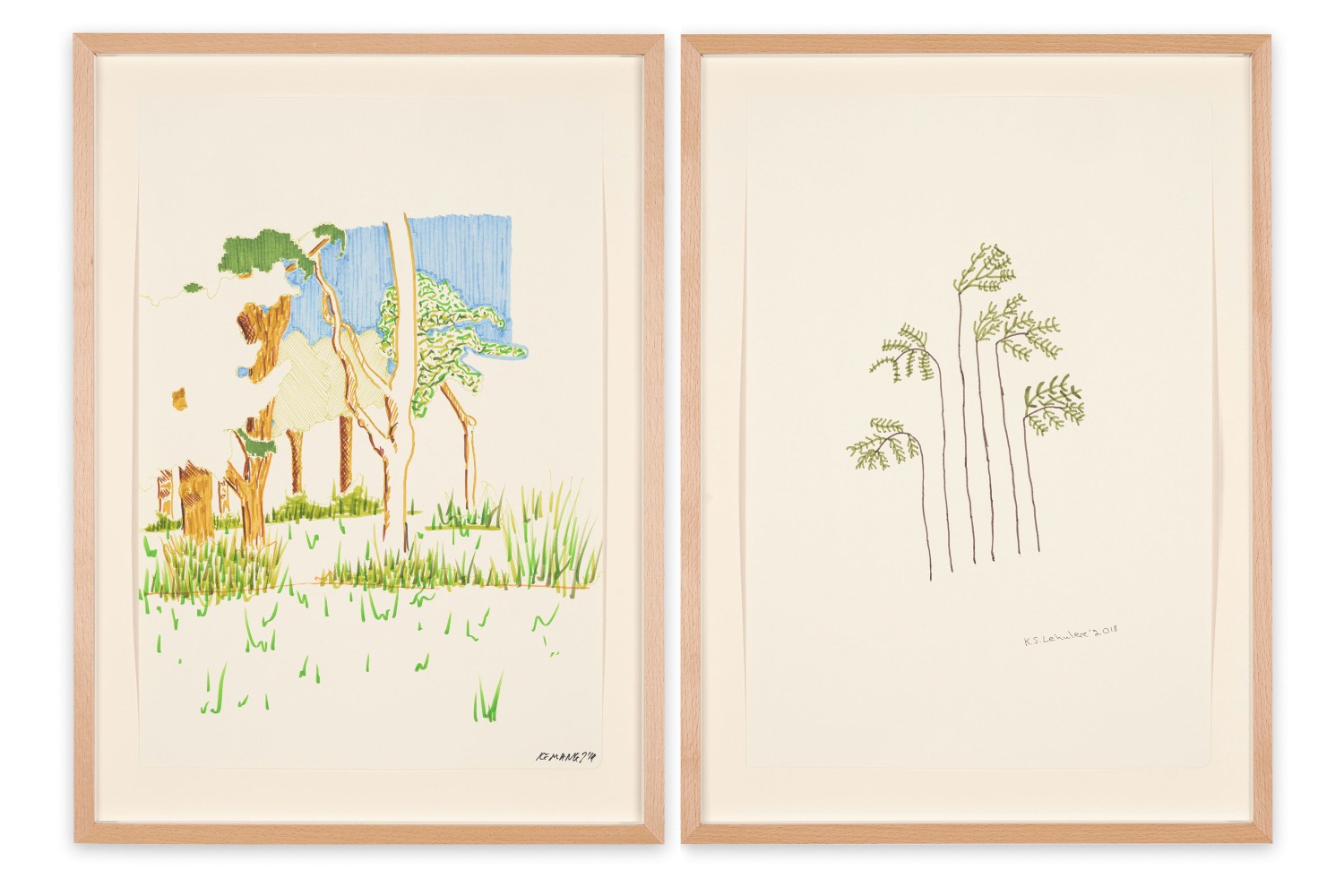

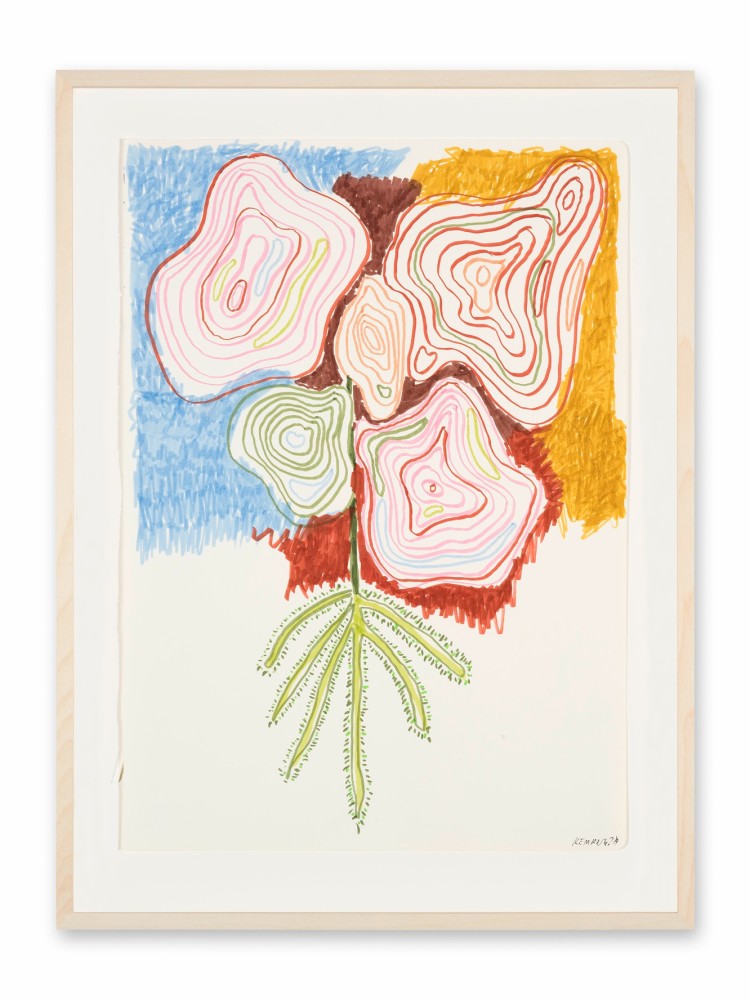

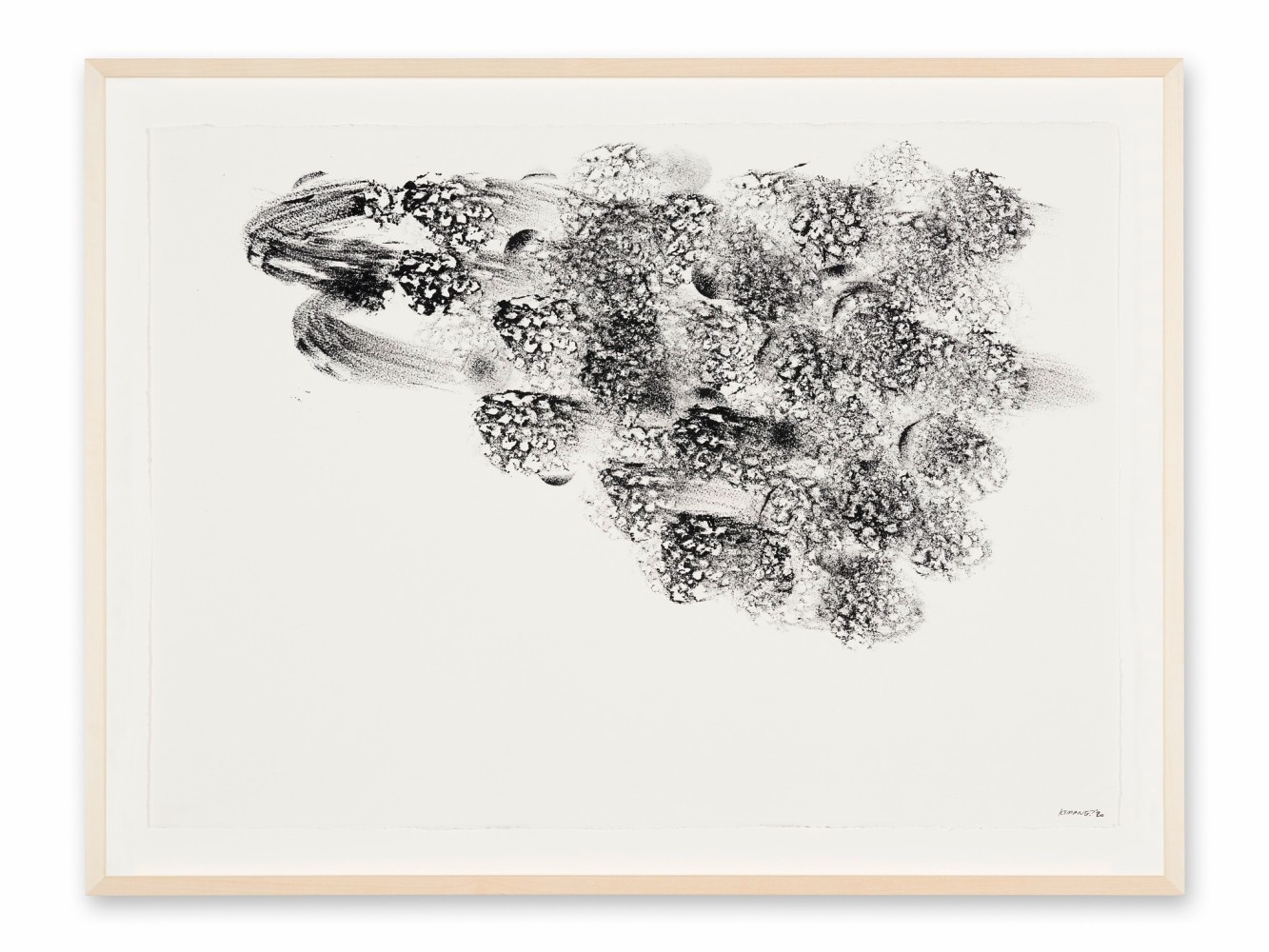

6/35

ink on paper

50.5 × 73 cm each (framed)

KW/D 45

7/35

ink on paper

50.5 × 73 cm each (framed)

KW/D 47

8/35

ink on paper

50.5 × 73 cm each (framed)

KW/D 48

9/35

16 bronze life size hands on 16 music stands, 10 bronze large hands, bronze dog head

size variable

KW/S 3

10/35

16 bronze life size hands on 16 music stands, 10 bronze large hands, bronze dog head

size variable

KW/S 3

11/35

16 bronze life size hands on 16 music stands, 10 bronze large hands, bronze dog head

size variable

KW/S 3

12/35

crutches from salvaged shool desk, car tyre, salvaged school chair, porcelain dog, bottle with sand, shoe laces

179 × 128 × 70 cm

13/35

porcelain dog, resin moulded hand, car tyre, crutches from salvaged school desk, salvaged school chair, shoe laces

79 × 60 × 134 cm

KW/S 16

14/35

salvaged school chair, crutches from salvaged school desk, car tyre, wooden trophy shield, resin moulded hand, porcelain dog, shoe laces

146 × 65 × 84 cm

KW/S 4

15/35

porcelain dog, resin moulded hand, car tyre, crutches from salvaged school desk, salvaged school chair, shoe laces

134 × 70 × 40

KW/S 15

16/35

concrete moulds, metal pipes, car tyre, porcelain dog, wooden board

87 × 105 × 50 cm

KW/S 13

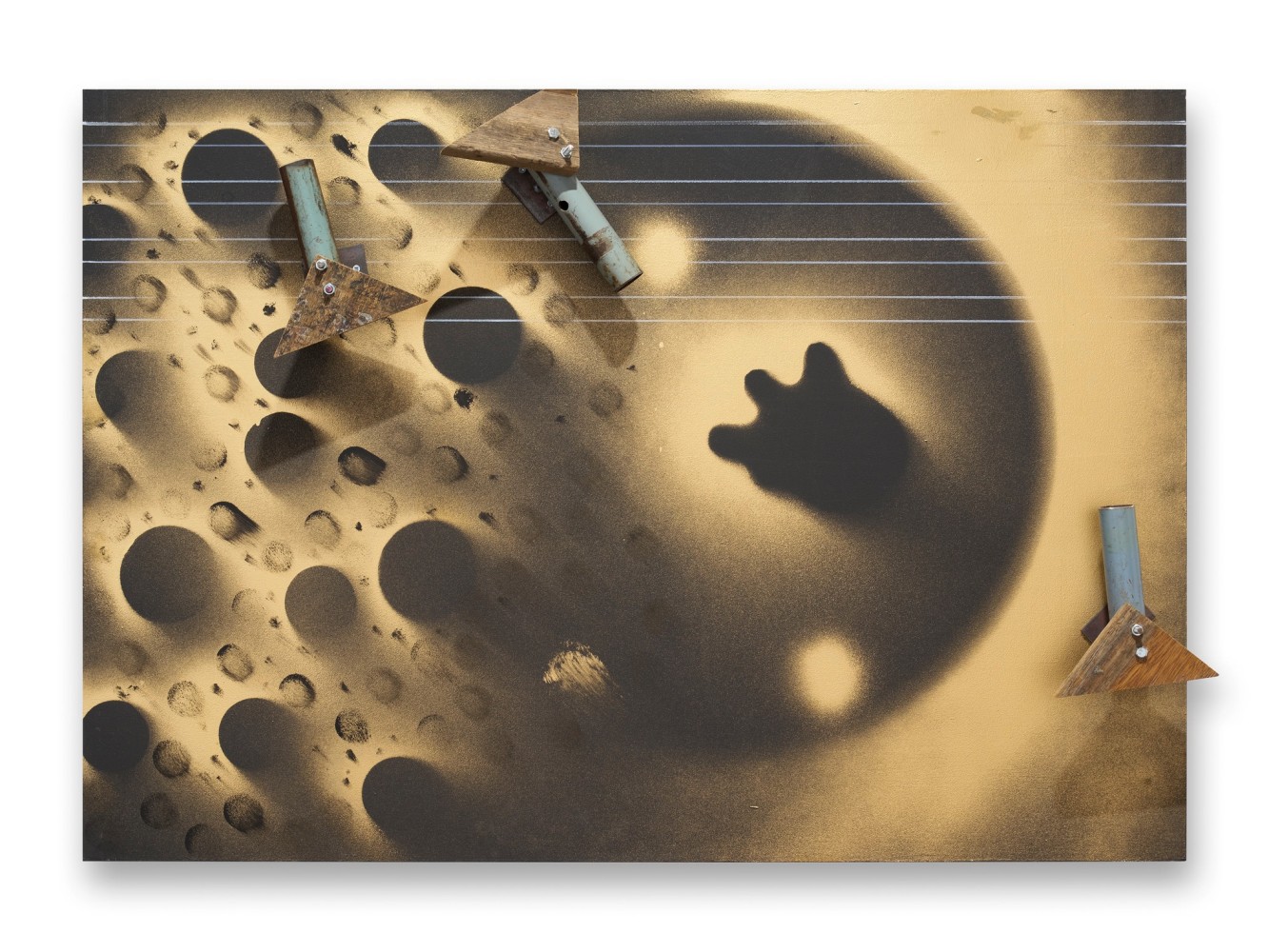

17/35

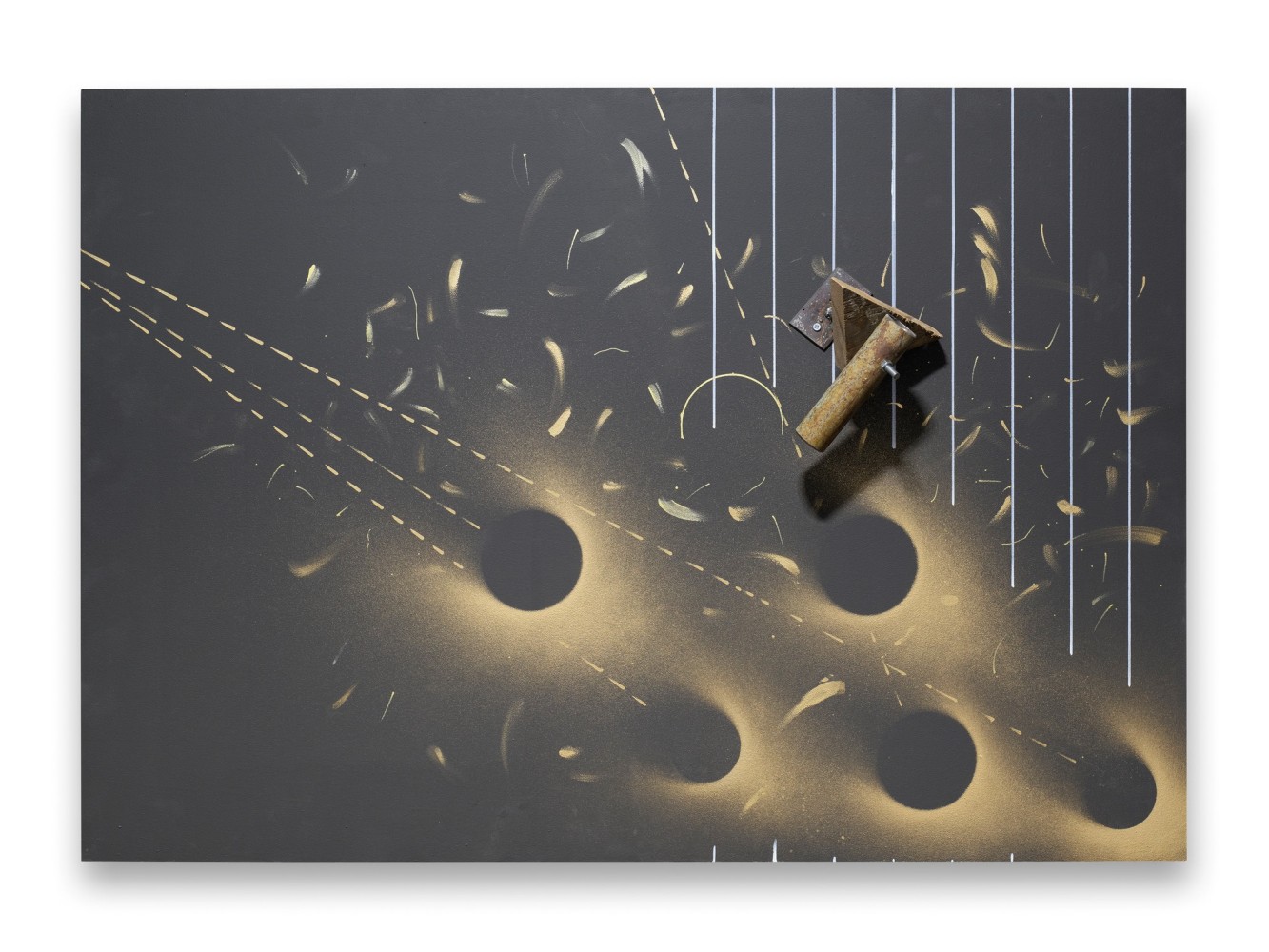

blackboard paint on MDF, metal wood

75 × 108.5 × 21 cm

KW/P 9

18/35

blackboard paint on MDF, metal, wood

70 × 100 × 11 cm

KW/P 13

19/35

ink on paper

112 × 83 × 3.5 cm (framed)

KW/D 24

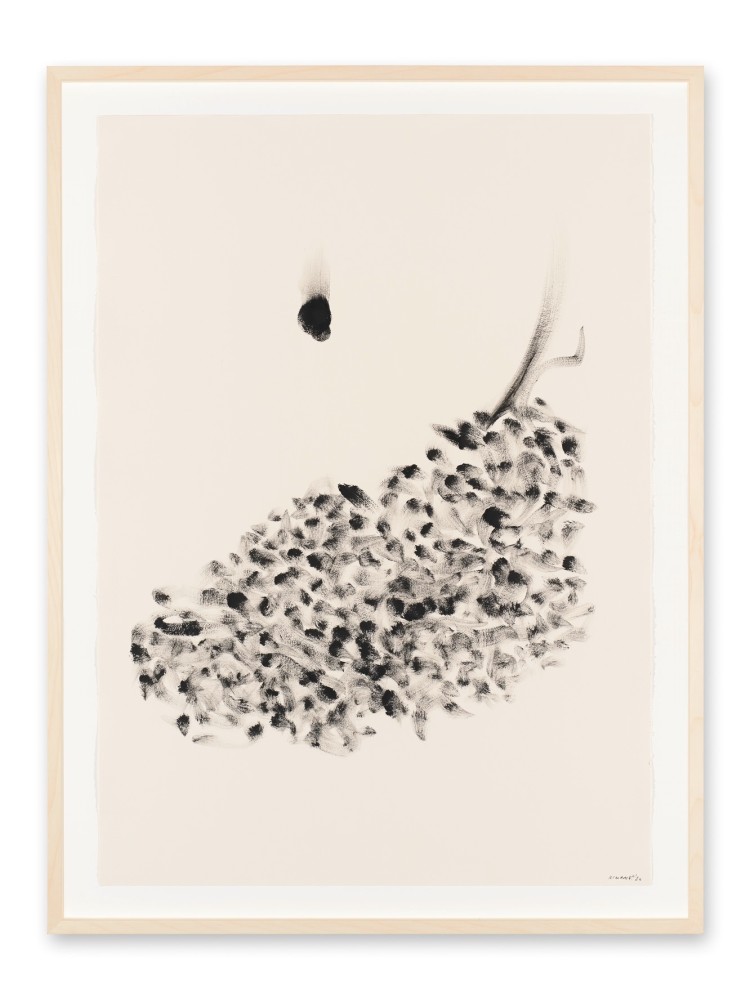

20/35

ink on paper

88 × 67 × 3.5 cm (framed)

KW/D 3

21/35

ink on paper

88 × 67 × 3.5 cm (framed)

KW/D 17

22/35

ink on paper

88 × 67 × 3.5 cm (framed)

KW/D 19

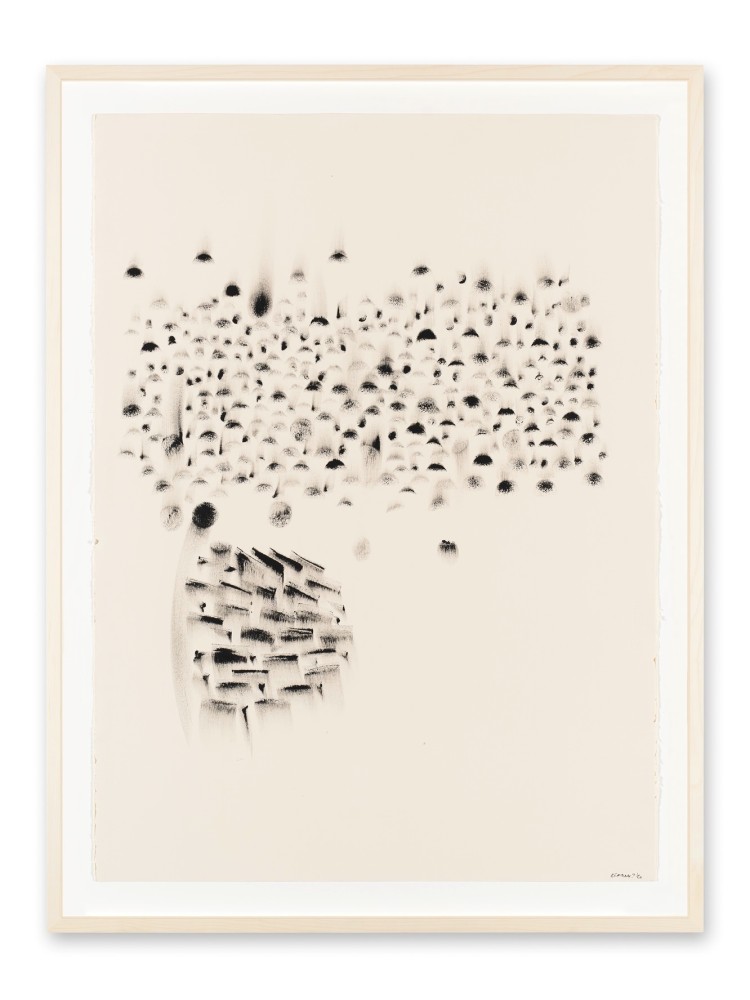

23/35

ink on paper

112 × 83 × 3.5 cm (framed)

KW/D 12

24/35

ink on paper

112 × 83 × 3.5 cm (framed)

KW/D 25

25/35

ink on paper

112 × 83 × 3.5 cm (framed)

KW/D 13

26/35

ink on paper

50.5 × 37.5 cm (framed)

27/35

ink on paper

50.5 × 37.5 cm (framed)

KW/D 34

28/35

ink on paper

50.5 × 37.5 cm (framed)

KW/D 33

29/35

ink on paper

50.5 × 37.5 cm (framed)

KW/D 30

30/35

blackboard paint on MDF, metal, wood

70 × 100 × 13.5 cm

KW/P 6

31/35

blackboard paint on MDF, metal, wood

70 × 104.5 × 22.5 cm

KW/P 8

32/35

blackboard paint on MDF, metal, wood

70 × 101 × 14.5 cm

KW/P 12

33/35

ink on paper

88 × 67 cm (framed)

KW/D 18

34/35

ink on paper

88 × 67 cm (framed)

KW/D 20

35/35

ink on paper

83 × 112 cm (framed)

KW/D 22

Group show

Heide Museum, Bulleen, Australia

04.05.–06.10.2024

Heide MuseumGroup show

Bündner Kunstmuseum, Chur

24.02.–28.07.2024

Bündner KunstmuseumGroup show

Fundació Es Baluard

Museu d’Art Modern i Contemporani de Palma

31.01.–24.05.2024

Fundació Es BaluardNkgopoleng Moloi

May 2023

“Art doesn’t have to solve problems, it only has to formulate them correctly,” as Anton Chekhov said. Kemang Wa Lehulere’s solo exhibition “Bring Back Lost Love” attempted to formulate the problem of loss and reclamation—of land, dignity, and ultimately, love.

Nkgopoleng Moloi

May 2023

“Art doesn’t have to solve problems, it only has to formulate them correctly,” as Anton Chekhov said. Kemang Wa Lehulere’s solo exhibition “Bring Back Lost Love” attempted to formulate the problem of loss and reclamation—of land, dignity, and ultimately, love. A gathering of drawings and mixed-media installations let us feel the weight of history.

Wa Lehulere’s works engage what he refers to as the “double lives” of objects, that is to say, the multiple ways a thing can be interpreted and reconfigured. This show took its impetus from the concept of love, bringing to mind bell hooks’s reflection, in the essay “Love as the Practice of Freedom” (1994), that “without love, our efforts to liberate ourselves and our world community from oppression and exploitation are doomed.” Wa Lehulere’s works likewise suggest that the struggle for liberation is founded on love.

Wa Lehulere’s sculptural installations collect the ghostly and haunted ephemera of our past: objects ranging from salvaged school desks, ceramic dogs, concrete, and plaster to shoelaces, glass bottles, sand, and chalk. Most refer to and reflect on colonial and apartheid history through the language of education and ubiquitous household objects. One wall of the white-cube gallery was painted emerald green, immediately drawing the viewer’s eye. This was the background to the installation Reddening of the Greens 2 (ii), 2021, in which found items such as crutches sticking out of old suitcases—emanating a sense of historical gravity that is recurrent in Wa Lehulere’s work—are mounted to the wall. In Conference of the Birds, 2017–21, fifteen birdhouses have been constructed out of sixteen salvaged school desks. Some upright, others upended, they are encircled by music stands and paper scrolls scattered on the floor and are guarded by life-size black-porcelain dogs, typical ceramic decorations found in the homes of many Black working-class families in South Africa. Here they are also reminders of the dogs used by apartheid-era police. They evoke familiarity and fear all at once.

Wa Lehulere’s practice participates in a kind of call-and-response with writers and artists who have influenced his thinking. One of his longtime inspirations is the great South African modernist painter Gladys Mgudlandlu, affectionately known as “Bird Lady” for her keen interest in painting avians. Perhaps Wa Lehulere’s birdhouses are sculpted to shelter these creatures. Mgudlandlu was also a schoolteacher and taught Wa Lehulere’s aunt Sophia Lehulere until they were forcibly removed from their homes in Athlone to Gugulethu—a result of the Group Areas Act, which designated certain areas as for whites only. The subtlest, most surprisingly delicate work in the exhibition was a series of ink drawings the artist made in collaboration with his aunt Sophia. These depict finely rendered flowers, trees, and forests— wonderful and serene landscapes inspired by hand-painted murals that famously adorned Mgudlandlu’s home.

In the five-page framed missive, Letter to the Nobel Committee, 2016, Wa Lehulere calls for a posthumous award to early-twentieth-century linguist Sol Plaatje for his book Native Life in South Africa (1916), which was written to protest the Natives Land Act of 1913. This law, which prohibited any purchase or lease of land by Black people outside of certain “native reserves” amounting to less than 13 percent of the country’s landmass, resulted in massive dispossession. Wa Lehulere’s letter performs a kind of utopian vision through which one social action might have launched a chain of events disrupting the sustained violence enacted on Black people in South Africa and pointing toward liberation. “Bring Back Lost Love” induced a feeling of being immersed in history and working through the ways in which narratives can be retold or reimagined: What would have happened if Plaatje had won the Nobel Peace Prize? Such speculations are not without real-world implications. Although its tone was not didactic, the exhibition offered moral instruction nonetheless.

Mathew Blackman

28 March 2023

Bring Back Lost Love at Blank Projects, Cape Town conjures the South African experience as an intellectual struggle against racism.

Mathew Blackman

28 March 2023

Kemang Wa Lehulere, Reddening of the Greens 2 (ii), 2021, salvaged school desks, crutches and found suitcases, 200 × 650 × 30 cm. Courtesy the artist

Bring Back Lost Love at Blank Projects, Cape Town conjures the South African experience as an intellectual struggle against racism

Kemang Wa Lehulere’s aesthetic is one born almost entirely out of a South African experience. In many ways Bring Back Lost Love is an attempt to conjure with the past through the everyday artefacts of the Black experience under apartheid, gathered and arranged in installations on walls, floors and tables throughout the gallery. In Reddening of the Greens 2 (ii) (2021), wall-mounted found objects including wooden crutches protruding from old suitcases summon the trials of migrant labourers and miners disabled from work in criminally unsafe conditions. Rural and township schools are suggested in Notes 1–13 (2017–21), a series of chalk and white-paint drawings on uniformly sized black boards lined up along gallery walls.Ceramic black German Shepherds scattered throughout his installations are perhaps the symbol of apartheid police brutality.

But Wa Lehulere is not simply working with the signifiers of repression; he also elicits the creative reaction to that oppression, summoning a Black intellectual tradition that was engendered by the likes of Solomon Plaatje, R.R.R. Dhlomo (both of whom he regularly mentions) and the half-Irish half-Herero Robert Grendon (Wa Lehulere’s father was also Irish). The exhibition is, on certain terms, an evocation of their intellectual struggle against racism, and a tradition that produced translations of Shakespeare, epic poetry, plays, novels and most importantly journalism and letters of passionate protest – most of which are now consigned almost to oblivion in South African archives.

Perhaps the most overt allusion to this forgotten tradition is Letter to the Nobel Committee (2016), handwritten on pages torn from a notebook and framed in several panels. The letter advocates for the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to writer and politician Plaatje. This is no frivolous artistic posture: even British prime minister David Lloyd George, who met Plaatje in 1919, noted that he was a hugely impressive leader of the early peace-seeking African National Congress (ANC).

Wa Lehulere intuitively reworks forgotten intellectual interests and concerns. His ink drawings of plants in ERF 1–18 (2019–21) can be seen as a surrogate for Grendon’s book on botany, The Illustrated Genera of South African Flowering Plants, referenced in contemporaneous sources but otherwise entirely lost to history. Grendon, who taught at the school of ANC leader Albert Luthuli (who did win the Noble Peace Prize) and was a fundamental figure in this South African Black intellectual tradition, is completely forgotten, without even a surviving photograph to represent him. It is precisely this form of elision and loss that Wa Lehulere, in Bring Back Lost Loves, provokes back into being.

Athi Mongezeleli Joja

2021

The title of Kemang Wa Lehulere’s exhibition “Where Did The Sky Go?” captures a sense of capriciousness and bewilderment. The disappearance of the sky causes panic. It is a disorienting absence. The image created in one’s mind can perhaps be read through the theological lens of the biblical pre-creation and calls to mind the absolute nothingness that defines it.

Seraina Peer

May 2021

Anhand seiner Herkunft thematisiert Kemang Wa Lehulere strukturelle und gesellschaftliche Probleme von globaler Aktualität. Die Ausstellung ‹Where Did The Sky Go?› besticht durch ihre Vielschichtigkeit und führt vor Augen, dass die Vergangenheit stets ein Teil der Gegenwart ist.

Seraina Peer

May 2021

Zuoz — Es ist kalt und grau. Ich wundere mich, wohin der sonst so blaue Engadiner Himmel verschwunden ist. ‹Where Did The Sky Go?›, fragt auch die Ausstellung des südafrikanischen Künstlers Kemang Wa Lehulere (*1984, Cape Town) in der Galerie Tschudi. Mit gefundenen, wiederverwendeten und neu zusammengesetzten Materialien erzählt sein Schaffen von Gewalt, Träumen und verstummten Stimmen, ohne dabei moralisierend zu wirken. Skurril und surreal erscheinen die Installationen aus Reifen, Stühlen, Krücken, Abgüssen von Hunden und Händen. Letztere werfen nicht nur die Frage auf, wer welche Fäden zieht – womit sie auf gesellschaftspolitische Abhängigkeits- und Machtverhältnisse anspielen mögen –, sie dienen auch als Kommunikationsmedium. So buchstabieren weisse Hände auf Notenständern per Fingeralphabet die Frage ‹Where Did The Sky Go?›, während schwarze Hände mit diffusen Zeichen eine Antwort verwehren. Auf komplexe Fragen gibt es eben keine einfachen Antworten. Die Sprache als Vermittlerin wird zur Zeugin ihres eigenen Versagens.

Indem der Künstler scheinbar harmlose Objekte aufgreift und in assoziativer - Weise zu neuen Konstellationen fügt, legt er tieferliegende kulturelle Bedeutungsebenen frei. Der Saaltext, verfasst vom südafrikanischen Kunstkritiker Athi Mongezeleli Joja, bietet Einblicke in die Apartheitsgeschichte Südafrikas und verbindet sie mit den symbolisch genutzten Gegenständen in Wa Lehuleres Installationen. So erhalten die Reifen als Instrumente für Lynchmorde und das damit verschränkte Schulmobiliar als Symbol eines repressiven Bildungssystems eine neue, bedrohliche Bedeutung. Doch auch ohne dieses Mehrwissen rufen die Werke ein Gefühl des Unbehagens hervor. Ambivalent wirken die ausgestellten Schäferhunde aus Porzellan. Sind sie Bedrohung, Schutz oder schweigende Zeugen? Welche Bedeutung nehmen sie in ihrer paradoxen Rolle als bevorzugte Hunderasse der Polizei während der Apartheid und Kitschobjekt in den Häusern der schwarzen Arbeiterklasse ein? Genauso ergreifend wie Wa Lehuleres Installationen sind seine Zeichnungen und Gemälde. Diesen wohnt – anders als den Objekten – eine tiefe poetischen Anmut inne. Die unterschwellige Brutalität hat einer lyrischen, traumhaften, fast hoffnungsvollen Komponente Platz gemacht. Ihre Werktitel erzählen von ‹Sky Dwellers›, einer ‹Celestial Cartography› und umrahmen mit ‹The Sky Sleeps in Your Eye› prägnant und eloquent den Kosmos der Ausstellung. Vielleicht ist das die Antwort auf die Frage nach dem verschwundenen Himmel.

Ian Bourland

30 October 2018

I cut my skin to liberate the splinter evokes the dissonance and precarity of post-apartheid South Africa

Sean O'Toole

12 March 2017

Today KEMANG WA LEHULERE is one of South Africa’s most important contemporary artists. But it was not an easy road. Sean O’Toole talked with him about successes and losses, transience and the Fall. A studio visit.

We are very sorry.

Unfortunately, your browser is too old to display our website properly and to use it safely.

If you are using Internet Explorer, we recommend updating to its successor Edge or switching to Firefox, Chrome or Brave. If you surf with Safari, we recommend updating or even switching to one of the above browsers.

Galerie Tschudi

Contact Page×